Do we expect too much from our children?

It is quite natural that we as parents want our children to do well and want the best for them. We worry about them all the time and we want them to be able to meet all the age appropriate targets.

“ My child is 2 years old, should I start potty training” “My 4 year old should be able to able to get dressed himself/herself” And “my 10 year old child should be able to sit down and concentrate on his homework without distractions”.

Parents also tend to expect behaviours before the child is developmentally ready. For example, they expect a toddler to share toys in play group, siblings to always get along, kids to remember what we said.

10243961 – the student with a considerable quantity of books

Our expectations of our children’s psychological abilities, even more than of their physical abilities, are typically much too high. I think we are being unrealistic and thus are we then putting too much pressure on our children?

The research shows that we consistently overestimate their self-control, ability to persevere and stay on task, consistency of performance, and social ability. It’s normal for a 2-year-old to have an outburst if he doesn’t get what he wants; it is quite normal for a 3-year-old to lose it if there’s an unexpected change in the bedtime routine; it’s normal for a 6-year-old to fail to keep absorbed on a tennis game for any length of time. We know this, and we know that each of these developmental stages will probably pass in a few months’ time, but, still, we stand over the child with index finger raised, an unpleasant edge in our voice, futilely repeating: “I said you’d get it later,” or “Why are you making such a big deal about your bedtime story?” or “Get your head in the game!”

Results of a survey show that

- 56% of parents believe kids have the impulse control to resist the desire to do something forbidden before age 3.

- 36% believe that kids under age 2 have this kind of self-control.

- 43% of parents think kids are able to share and take turns with other kids before age 2.

- 24% of parents believe kids have the ability to control their emotions, like resisting tantrums when they’re frustrated, at 1 year or younger.

The truth however is different

- Self-discipline/ self-control develops between 3½ and 4 years, and takes even more years to be used consistently.

- Sharing skills develop between 3 to 4 years.

- Emotional control also won’t develop until between 3½ and 4 years.

Parents want to set high standards for their children and do all they can to help them to achieve what they’re capable of. But sometimes they can go too far. There is a very thin line between encouraging good performance and pushing too hard? The warning signs that the parent is going too far are

- Your child will start to lose interest in things they once loved. For example, If your little boy who used to love tennis but suddenly has lost interest in it, it may be because the pressure from you is too much. You need to have an honest talk to see if the heat from you or your spouse has burned him out.

- Your child will stop sharing fears and failures with you. You may find that your child is hiding her not-so-stellar moments from you. They may feel that you will be too disappointed or angry. Kids need to feel like their parents are a “safe place” where they can retreat to regroup after a failure.

- If your child is showing signs of weariness or regular moodiness, then that means they are overburdened. Over-scheduled kids who are pushed hard by their parents to do multiple activities often have their psychological stress surface as

physical symptoms or emotional behaviour. If your child is often worn-out or down, it may be because he is doing too much, or the pressure is too great.

physical symptoms or emotional behaviour. If your child is often worn-out or down, it may be because he is doing too much, or the pressure is too great. - When parents get too wrapped up in the success of their kids, it drains the pleasure out of the activities for everyone. Learn to just watch and enjoy without constantly assessing what your child could do better.

- Your child feels that your acceptance of them is tied to their performance. If the only time you praise your child or show them affection is when she achieves something, they will grow up seeing a direct relationship between the two. Make sure you remind your kid that you’d love them just as much if they never won a thing.

- If you are more concerned with the outcome than the process, then your child will feel the pressure. Being more concerned with the straight A’s or a certificate of excellence than with how the process of striving to do well is shaping your child’s character and work ethic is not going to be very encouraging for your child. A “B” that’s been hard-won is worth more than a thousand easy A’s, and a third-place finish that was formative for your child may be worth much more than that certificate of excellence.

To sum it up when we enforce unreasonable expectations on our children we are putting stress on them who respond by avoiding, escaping, and becoming irritable.

First, aim to build towards success gradually, and focus on trying to do what’s valuable, not on immediately reaching the level of performance you think a child of that age should reach. If you come across strong resistance, then leave it for few days, and when you return to the issue, lower your expectations. Seek to get the desired behaviour for a shorter period, ask for less of it. Working up to the desired behaviour gradually, in doable steps, is a process called shaping.

If we take an example that your child is behind in reading compared to rest of his class. His teacher wants you as the parent to do some extra reading with him/her at home every day for 15 minutes. Your child, who’s self-conscious about his reading, resists this “extra” work, perceiving it as a penalty. The resistance, on top of the reading problems, produces a situation that can make a parent frustrated and angry and in turn make the child anxious. A more sensible approach to this will be is to try something low-key, like, “We’re going to read to each other in turns of 2 minutes each. Once your child and you have got the habit in place, over a week or two you can escalate in easy stages up to 15 minutes of reading.

Your child’s resistance to learning to read may be either his genuine difficulty with reading so by your putting additional pressure on him you are increasing your stress levels. As your stress goes up, it’s very likely that your increased stress will translate into behaviour (such as harsh categorical statements) that will cause your child’s stress to go up when you try to get him to work on his reading. So, it is very crucial that you help your child with the reading without putting the pressure.

If you find yourself saying, “No matter how hard I try and try, I can’t make my kid do A …” or “No matter how hard I try, I can’t make my kid understand B …” it’s usually is a clear sign that your expectations are too high and you need to readdress the way you are handling it.

When your child fails to meet a specific and clear request and it’s a one-time occasion, try to let it go if you can. But if the request is not met and it’s not a one-time event, then it’s time to begin shaping the desired behaviour. Start in small chunks and keep increasing until you reach the point you are happy to settle for: less behaviour, for less time, less often. For example, you could start by doing ten minutes of homework and slowing increasing the time, not making them sit doing homework for a full hour right away; putting their toys away, not cleaning their whole room. Then work up to the desired level. And, once you get close, remember that getting a behaviour to occur most of the time, as opposed to every single time, is probably good enough. Exceptions are usually not a problem; they’re normal.

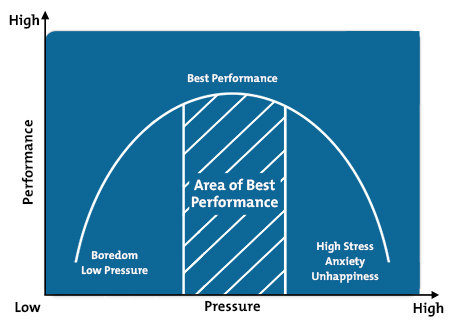

Finally, I would like to tell you about and ask you to bear in mind the principle of the U-shaped relation.

The Inverted-U model (also known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law), was created by psychologists Robert Yerkes and John Dodson as long ago as 1908. Despite its age, it’s a model that has stood the test of time.

It shows the relationship between pressure (or arousal) and performance.

According to the model, peak performance is achieved when people experience a moderate level of pressure. Where they experience too much or too little pressure, their performance declines, sometimes severely.

The left-hand side of the graph shows the situation where people are under-challenged. Here, they see no reason to work hard at a task, or they’re in danger of approaching their work in a “sloppy,” unmotivated way.

The middle of the graph shows where they’re working at peak effectiveness. They’re sufficiently motivated to work hard, but they’re not so overloaded that they’re starting to struggle. This is where people can enter a state of “Flow,” the enjoyable and highly productive state in which they can do their best work.

The right-hand side of the graph shows where they’re starting to “fall apart under pressure.” They’re overwhelmed by the volume and scale of competing demands on their attention, and they may be starting to panic.

The good news is that you are the expert as far as your child is concerned. Just remember that the line between encouragement and pushing is a little blurred- If you are constantly encouraging your child to do well it may become somewhat a pushy exercise and do more harm than good. You should support your children and inspire them to do well but don’t nag on and show your disappointment if they fail, as your kid wants to know that you are proud as long as they try their very best.

Namita Bhatia

NLP4Kids Practitioner at Kids Mindset Therapy Ltd

http://childtherapypinner.nlp4kids.org/

Leave a Reply